At midnight on October 21, Ireland introduced its highest level of national restrictions as part of a lockdown that will last six weeks. In the days that followed, many other European countries did the same, from France to Germany, Wales and Belgium. England will shortly follow suit.

As is the case for many of these countries, the Irish restrictions are not quite as severe as during the first lockdown in March, as schools have remained open and larger numbers are permitted at funerals and weddings.

So why did Ireland have to do this, and will the first European country to go into a new lockdown be able to conquer the second wave of coronavirus?

Spring vs autumn

Although serious, the situation in Ireland is different to how it was in spring. Far more testing is being done, including testing suspected cases with a wider range of symptoms, testing asymptomatic contacts, and mass testing high-risk workplaces and care facilities. As in many countries, more cases are now occurring in younger people.

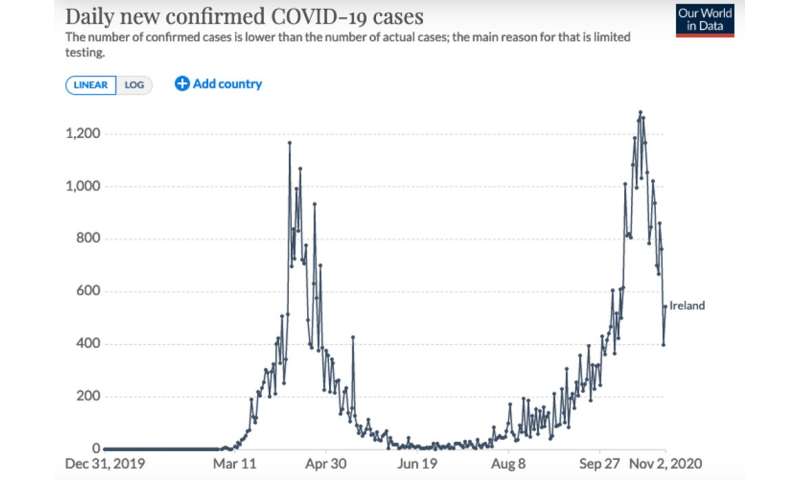

This change in testing means it’s not possible to accurately compare the rates now with the rates in March-April when Ireland was only testing those with several symptoms. Allowing for this, however, it is clear that as soon as community numbers began to rise after the first lockdown ended, the low hospitalisations and ICU admissions the country had achieved began to rise again quickly as older people became more exposed to infection.

In the days after level 5 restrictions were imposed, ICU admission rates were the highest since May. There are outbreaks in nursing homes again. And we must not forget that, although rare, there can be serious complications from COVID-19, even in young people.

The first in Europe

International comparisons of rates of COVID-19 are difficult for many reasons. Differences in testing policy, which shifts quickly, hospital capacity, ICU beds and prevalence of underlying health conditions all make for challenges in comparison. Nonetheless, when the restrictions were announced, Irish politicians were criticized for imposing a lockdown classed as the “strictest in Europe.”

However, last week Mike Ryan of the World Health Organization warned that the whole continent was lagging in its response to COVID-19. “There’s no question that the European region is an epicenter for disease right now,” he said. “Right now we are well behind this virus in Europe so getting ahead of it is going to take some serious acceleration in what we do and maybe much more comprehensive nature of measures that are going to be needed.”

This is precisely what Ireland is doing, and others have since followed suit. France and Germany are now in similar lockdowns, as cases soar in those countries. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson has announced that England will go into lockdown on November 5, while Wales started its own “firebreak” lockdown on October 19.

Perhaps the most interesting comparison is with Northern Ireland, which began its “circuit breaker” lockdown on October 16, due to last four weeks. Given the nature of the open border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, an all-island basis approach to public restrictions would have been ideal as those counties near the border have suffered most from different practices, with huge surges of infections recently.

Will it work?

There have been challenges in the response to COVID-19 in Ireland. The recent exponential rise in testing and positive cases has meant that waiting times for tests were prolonged, and for a short time contact testing services were overwhelmed; almost 2,000 COVID-19 cases were asked to alert their own contacts. There also has been insufficient recruitment to support contact tracing.

Testing turnaround had improved when cases were low, but that too was soon overwhelmed when the number of tests requested increased dramatically—for example, with a 6% positivity rate on October 10, for every positive test there were 16 that were negative but still had to be processed. The positivity rate has now been brought down to 4.8%.

Laboratory testing staff meanwhile are not immune to coronavirus as was seen in the recent closure of the National Virus Reference Laboratory for two weekends with several staff absent due to COVID-19.

Since the pandemic began, patients have been worried about attending the hospital and GP, and there are fears that presentation with diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease have been seriously delayed. The effect of this will only truly be seen after the pandemic is over. Hospitals need to be able to do what they normally do—treat non-COVID disease. ICU beds are needed for other patients.

I hope this period of high-level restrictions will be the short sharp shock Ireland needs to get back on track. The six-week duration is designed to ensure that Ireland can truly suppress the virus, and anything less would probably not be enough. Coronavirus incubation is five days on average but can be up to 14. A full two weeks will have to have elapsed before it is clear whether there has been a drop in cases.

Time will tell how effective Ireland’s lockdown will be, and its success depends on everyone complying with the restrictions—something that is more difficult the second time around. Coronavirus fatigue is present. But there are positive early signs: Ireland is one of only four countries in Europe where the seven-day incidence rate of COVID-19 has decreased compared with last week.

Over the coming weeks, it is essential that our politicians, Department of Health and Health Service Executive plan properly for reopening society following the lockdown. Besides suppressing infection rates, this lockdown must be used to recruit more contact tracers, provide faster turnaround times for test results, provide greater support for public health departments—as well as improving our ICU capacity—as we wait and hope for a vaccine.

Source: Read Full Article