If you have sex now, had sex in the past or will have sex in the future, there’s an excellent chance you’ve had, have or will someday get human papillomavirus (HPV), the sexually transmitted infection that is linked to several cancers. In fact, as many as 80 percent of people in the U.S.—women and men—will at some point contract HPV, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The good news: The next generation of children and young adults may not face these odds thanks to the HPV vaccine. The CDC recommends vaccinating girls and boys at age 11 or 12, before they become sexually active, to help prevent the rampant transmission that has come to define HPV.

But due to controversy about vaccinating young people against a sexually transmitted infection and parental concerns about possible long-term effects of these relatively new vaccines, many children, teens and young adults aren’t getting vaccinated, leaving them vulnerable to future HPV infection. Also, research has shown that getting the HPV vaccine does not encourage kids to become sexually active or start having sex at a younger age—a common concern cited by parents.

Here Karen Lui, MD, a pediatrician at Rush, shares eight more things you should know about HPV and the vaccine.

1. HPV is easy to get.

“People can contract HPV during their first sexual encounter or their 20th, and they can get it even if they’ve been monogamous and had sex with only one person,” says Lui. “It’s so common.”

With few visible symptoms, people often don’t even know if they are infected—leaving their partners at risk for contracting HPV as well. “It’s a stealthy infection,” says Lui. “That’s why prevention is so important.”

The vaccine is critical to widespread prevention. A study in Pediatrics found that since the vaccine was introduced in 2006, vaccine-type HPV prevalence decreased 64 percent among females ages 14 to 19.

The HPV vaccine protects more than just your child; it affects your entire community. “The vaccine can help prevent your child from both contracting HPV and spreading the virus to others,” says Lui. “So when you protect one child with the vaccine, you’re protecting others.”

2. HPV is incurable and can cause cancer.

Most HPV infections clear up on their own within two years, with no long-term consequences.

But other times, the infection does not clear up. And since there is no cure for HPV, the virus puts people at risk for potentially serious problems—such as cancer and genital warts—down the road.

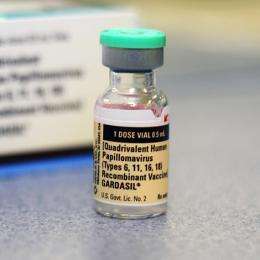

Of the more than 40 strains of HPV, there are nine specific strains—6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58—that the vaccine prevents. These strains cause genital warts and cancer.

Every year, more than 27,000 women and men are affected by the following cancers linked to HPV:

- Anal cancer

- Cervical cancer

- Oropharyngeal cancer, which includes oral cancer and throat cancer

- Penile cancer

- Vaginal cancer

- Vulvar cancer

Almost all cervical cancers are caused by HPV, and 72 percent of oral cancers (particularly in young men) are caused by HPV. According to the CDC, most of these HPV-related cancers could be prevented by vaccinating children before they become sexually active adults.

3. Vaccinate early if there is a family history of cervical cancer.

While 11 is the average age children get vaccinated, you might consider getting your child vaccinated around age 9 if you have a family history of cervical cancer—including your child’s mother, grandmothers and aunts.

Lui recommends talking to your pediatrician or primary care doctor if there’s a history of cervical cancer.

4. Boys should also be vaccinated.

In addition to preventing genital warts, studies have shown that the HPV vaccine can help prevent anal cancer in men. Preliminary research has also found that the HPV vaccine may protect against penile, oral and throat cancers—which are on the rise in young men.

“By 2020, HPV is projected to cause more oropharyngeal cancers than cervical cancers in the U.S.,” says Lui.

Another important reason to vaccinate boys is to protect the community at large. “If you vaccinate boys, you can help prevent them from contracting HPV infection and, subsequently, from spreading it to their current and future sexual partners. When you protect boys, you’re also protecting girls and vice versa,” Lui says.

5. The vaccine helps the body produce antibodies to fight HPV.

When the HPV vaccine (which is inactive and cannot cause HPV) is injected, your body will try to respond to it by making antibodies to fight the virus. Those antibodies will safeguard you against HPV infections.

In their preteen years, kids have a stronger immune response to the HPV vaccine. It is also more effective if the three-shot series, which is given over six months, is complete before children become sexually active.

6. The side effects are generally mild.

For the majority of healthy children, the HPV vaccine is safe, according to Lui. The most common side effects mirror those of other vaccines: pain at the injection site, fever and/or headache.

“I’ve had the HPV vaccine, and I wouldn’t recommend something for your child that I wouldn’t get myself,” Lui says.

7. HPV vaccines go hand-in-hand with screening and condoms.

In addition to getting vaccinated, Lui stresses the importance of using condoms. “The vaccine and condoms should go hand-in-hand,” she says. “Both are excellent ways to prevent the spread of HPV, but neither one is 100 percent.”

While studies have shown that using a condom properly and consistently—meaning every single time you have sex—can reduce HPV transmission, any area of the penis not covered by the condom can be infected by the virus.

“While the infection is most commonly passed by vaginal or anal sex, you can also transmit it during oral sex and skin-to-skin contact, and in those cases a condom isn’t going to protect you at all,” says Lui. “That’s where the vaccine can help safeguard you.”

Additionally, Lui recommends annual PAP tests for women starting at 21 years of age—whether they’ve been vaccinated or not. “Screening is the best way to catch HPV-related cancers early,” she says. At this point, there are no recommended routine screening tests for HPV-related cancers other than cervical cancer.

8. It’s important to have open conversations with your child about the HPV vaccine.

Lui encourages kids and parents to have an ongoing, open conversation about their wishes when it comes to being vaccinated.

“It’s hard for some kids to admit to their parents that they’re sexually active or are considering it,” says Lui. “But it’s important to be honest with your parents and tell them that you want to protect yourself.”

Source: Read Full Article