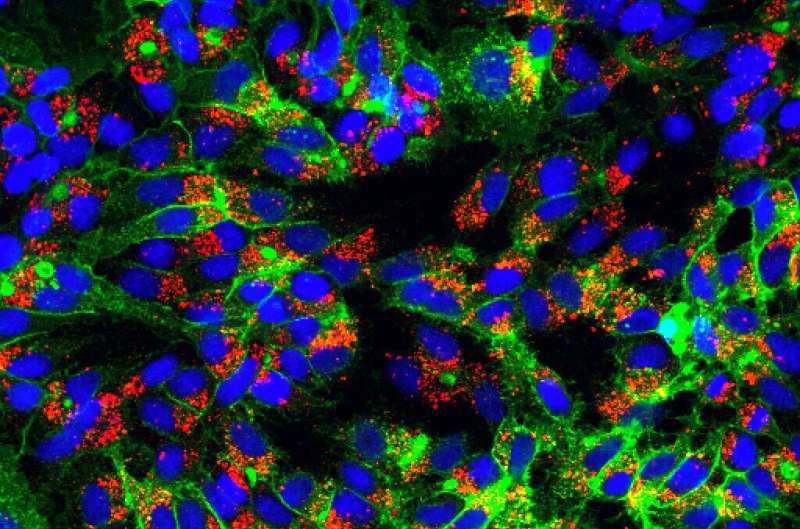

Researchers at Princeton have determined how five cellular proteins contribute to an essential step in the life cycle of hepatitis B virus (HBV). The article describing these findings appeared March 11, 2021 in the journal Nature Communications.

Viruses have been with us, shaping our lives, societies and economies for millennia. While some viruses rapidly explode onto the world stage, others smolder in our communities for decades, shattering lives but making few headlines. Hepatitis B virus hasn’t caused any nationwide lockdowns or stock market crashes because it is slow to spread from person to person and is rarely immediately fatal. It is nonetheless incredibly damaging because it can establish lifelong chronic infection with profound consequences for its victims.

“An estimated two billion people have been exposed to HBV, of whom 250-400 million are chronically infected,” said Alexander Ploss, associate professor of molecular biology at Princeton University, and senior author on the study. “Currently, there is no cure for chronic HBV infection, and patients need to be on a lifelong antiviral regimen. Approximately 887,000 individuals die each year from HBV-related liver diseases or liver cancer.”

Ploss and his team are striving to understand HBV’s life cycle in hopes of finding a way to prevent the virus from establishing damaging chronic infections.

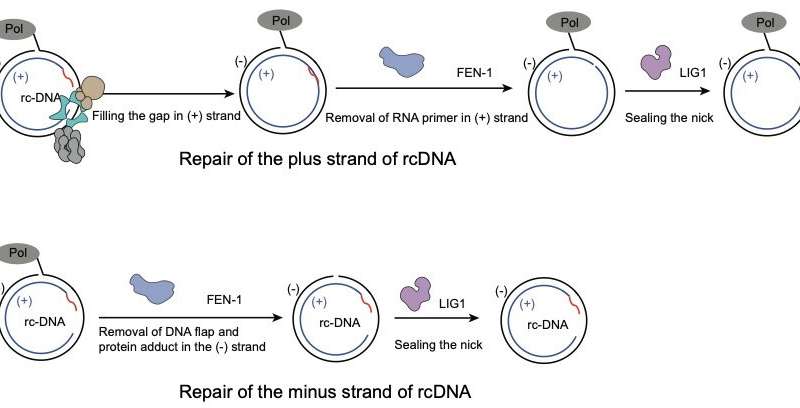

“Central to HBV replication is the formation of covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) from relaxed circular DNA (rcDNA) which is carried into the host cell by the virus during the initial infection,” Ploss said. “We have recently demonstrated that HBV relies on five host proteins—namely PCNA, RFC complex, POLδ, FEN-1, and LIG1—that are necessary and sufficient for this conversion step.”

As its name implies, rcDNA is a loop of DNA. DNA is a molecule made up of nucleotides arranged in linear fashion along paired, complementary strands. The sequence of nucleotides on one strand encodes the instructions for making a protein while the other strand is its mirror image. Whereas human cellular DNA contains over 20,000 genes, HBV’s DNA genome only contains four. None of the viral proteins made from these genes is required for the conversion of rcDNA to cccDNA. Instead, the virus coopts cellular proteins to accomplish this and other steps of viral replication.

A key feature of HBV rcDNA is that each of its two strands contains a gap in its nucleotide sequence. One strand, called the plus strand, has a gap that is considerably larger than and offset from the gap on the other, minus strand. Cells perceive gaps in DNA as damage that needs to be filled in and repaired. The cellular proteins that carry out DNA repair can’t tell the difference between viral DNA and cellular DNA, so they set to work “repairing” rcDNA as soon as it arrives in the nucleus. This repair process converts rcDNA into an intact circle of double-stranded DNA (that is, cccDNA) that can be maintained in the cell’s nucleus.

Postdoctoral fellow Lei Wei wanted to understand how this repair process takes place in detail. To investigate this, he developed a method to monitor the process of repair taking place on rcDNA. He then identified what steps are involved in repair of each individual strand, tracked the order in which they are completed, and determined which cellular proteins are needed for each step.

The experiments showed that conversion of the plus strand into a continuous circle happens rapidly and requires all five of the cellular proteins working in concert. In contrast, repair of the minus strand requires only two of the five proteins (FEN-1 and LIG1) but is slower because there is a viral protein attached to one end of the minus strand that must be removed before the nucleotide gap can be sealed.

“In this paper, Wei and Ploss provide a compelling story in elucidating the cellular machinery that is essential for converting the incoming HBV genome into the cccDNA,” said Dr. T. Jake Liang, a National Institutes of Health Distinguished Investigator in the Liver Diseases Branch who is an expert on HBV and related viruses. “This work offers not only important insights into the biochemical pathway of cccDNA biogenesis but also potential strategies to target cccDNA for therapeutic development.”

Furthering that goal, the Princeton researchers showed that two compounds targeting cellular proteins could disrupt rcDNA conversion to cccDNA in test tubes. Wei and Ploss are hopeful that future studies will identify drugs that work in the human body.

Source: Read Full Article