A study of large-scale functional brain network organization and educational history, led by researchers at the Center for Vital Longevity (CVL), has identified a new biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease. The findings, published online this week in Nature Aging, describe how declines in a measure of brain network organization precede cognitive impairment in older adults. Researchers also found that brain network declines are greater among individuals without a college education, suggesting that there are aspects of an individual’s environment that may accelerate brain aging.

“What’s exciting about this study is that we’ve identified a measure of brain function that seems to be sensitive to an individual’s past and present environmental exposures during adulthood. That brain network organization is also uniquely related to the prognosis of dementia, which opens up the possibility of incorporating the measure with other markers of Alzheimer’s disease risk and pathology in a clinical setting,” says Dr. Gagan Wig, director of the Wig Neuroimaging Lab at the CVL and associate professor at The University of Texas at Dallas.

It is well known that older adults with lower education levels are at a greater risk of dementia. But it’s unknown why some are more likely to develop dementia than others. The results from this study shed light on an important biomarker of clinical decline by showing that the trajectory of a person’s brain network organization varies according to their educational attainment, and is a unique indicator of individual brain health during older age.

“We’ve been working on this measure of brain network organization for a long time, and we knew it varied in relation to age and cognitive ability, but we were unsure how it changed over time in individuals or whether this would relate to changes in their cognitive health. We now have evidence that changes in brain network organization have a relation to cognitive decline in older age adults,” says the study’s first author, Dr. Micaela Chan, a postdoctoral scientist in Wig’s lab.

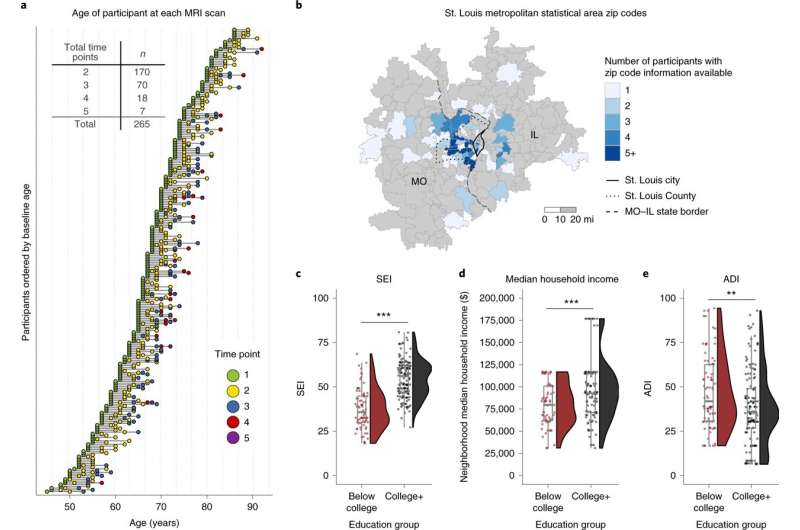

The study analyzed existing data that includes adults between the ages of 40 to 80, who received two to five MRI scans, and multiple clinical visits (the latter up to 10 years after the participant’s last MRI). Researchers examined the relationship between the participant’s education levels and changes in brain network organization over time while also accounting for demographics and various measures of health and pathology.

Brain network changes were evaluated in relation to the trajectories of clinical decline. While there are other known predictors of the development of Alzheimer’s disease, such as a person’s genetics and pathology, not everyone who has genetic risk or even the presence of pathology exhibits symptoms of dementia. However, the brain network measure changes observed in this study were independent of these other known risk markers, which suggests it contains unique information.

Importantly, the researchers found that the relationship between brain network decline and cognitive impairment was observed regardless of an individual’s education, revealing that there are more specific aspects of an individual’s environment that modify the brain’s network organization.

“We used education levels as an indicator of an individual’s environment because it represents things such as access to resources and health behaviors; although it is a coarse measure, it predicts a lot of important life outcomes,” says Chan.

Establishing a link between education levels and specific brain changes during older age is not only an important step toward understanding environmental determinants of brain disease but could also lead to the discovery and incorporation of brain network organization as a biomarker of brain health

Source: Read Full Article