By bringing DNA sequencing out of the sequencer and directly to cells, scientists from the McGovern Institute for Brain Research, the Harvard University Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology (HSCRB), and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have revealed an entirely new view of the genome. With a new method for in situ genome sequencing reported in Science, researchers can, for the first time, see exactly how DNA sequences are organized and packed inside cells.

The approach—whose development was led by McGovern Institute investigator and Broad Institute associate member Ed Boyden, and HSCRB faculty member and Broad associate member Jason Buenrostro, and HSCRB faculty member and Broad core institute member Fei Chen—integrates DNA sequencing technology with microscopy to pinpoint exactly where specific DNA sequences are located inside intact cells. While alternative methods allow scientists to reconstruct structural information about the genome, this is the first sequencing technology to give scientists a direct look. The technology creates new opportunities to investigate a broad range of biology, from fundamental questions about how DNA’s three-dimensional organization affects its function to the structural changes and chromosomal rearrangements associated with aging, cancer, brain disorders, and other diseases.

“How structure yields function is one of the core themes of biology,” Boyden said. “And the history of biology tells us that when you can actually see something, you can make lots of advances.” Seeing how an organism’s genome is packed inside its cells could help explain how different cell types in the brain interpret the genetic code, or reveal structural patterns that mean the difference between health and disease, he said. Additionally, the researchers noted, the technique also makes it possible to directly see how proteins and other factors interact with specific parts of the genome.

The new method builds on work underway in Boyden and Chen’s laboratories focused on sequencing RNA inside cells. Buenrostro collaborated with the two scientists to adapt the technique for use with DNA. “It was clear the technology they had developed would be an extraordinary opportunity to have a new perspective on cells’ genomes,” he said.

Their approach begins by fixing cells onto a glass surface to preserve their structure. Then, after inserting small DNA adapters into the genome, thousands of short segments of DNA—about 20 letters of code apiece—are amplified and sequenced in their original locations inside the cells. Finally, the samples are ground up and put into a sequencer, which sequences all of the cells’ DNA about 300 letters at a time. By finding the location-identified short sequences within those longer segments, the method pinpoints each one’s position within the three-dimensional structure of the cell.

Sequencing inside the cells is done more or less the same way DNA is sequenced inside a standard next-generation sequencer, Boyden explained, by watching under a microscope as a DNA strand is copied using fluorescently labeled building blocks. As in a traditional sequencer, each of DNA’s four building blocks, or nucleotides, is tagged with a different color so that they can be visually identified as they are added to a growing DNA strand.

Boyden, Buenrostro, and Chen, who began their collaboration several years ago, said the new technology represents a heroic effort on the part of MIT and Harvard graduate students Andrew Payne, Zachary Chiang, and Paul Reginato, who took the lead in developing and integrating its many technical steps and computational analyses. That involved both recapitulating the methods used in commercial sequencers and introducing several key innovations. “Some advances on the technology side have taken this from impossible to do to being possible,” Chen said.

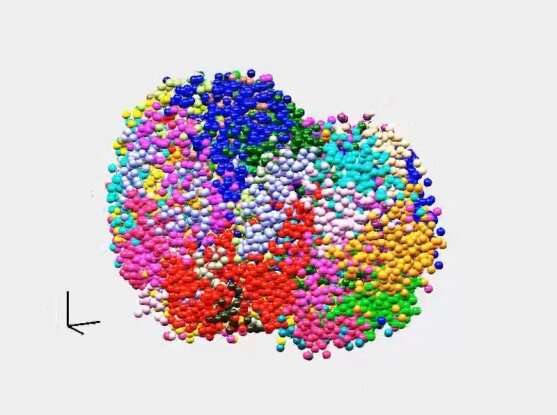

The team has already used the method to visualize a genome as it reorganizes itself during the earliest moments of life. Brightly colored representations of DNA that they sequenced inside a mouse embryo show how genetic information inherited from each parent remains distinct and compartmentalized immediately after fertilization, then gradually intertwines as development progresses. Their sequencing also reveals how patterns of genome organization, which very early in life vary from cell to cell, are passed on as cells divide, generating a memory of each cell’s developmental origins. Being able to watch these processes unfold across entire cells instead of piecing them together through less direct means offered a dramatic new view of development, the researchers say.

Source: Read Full Article