The quest to find an anticoagulant that can prevent strokes, cardiovascular events, and venous thrombosis without significantly increasing risk of bleeding is something of a holy grail in cardiovascular medicine. Could the latest focus of interest in this field – the factor XI inhibitors – be the long sought after answer?

Topline results from the largest study so far of a factor XI inhibitor ― released last week ― are indeed very encouraging. The phase 2 AZALEA-TIMI 71 study was stopped early because of an “overwhelming” reduction in major and clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding shown with the factor XI inhibitor abelacimab (Anthos) compared to apixaban for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

Very few other data from this study have yet been released. Full results are due to be presented at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions in November. Researchers in the field are optimistic that this new class of drugs may allow millions more patients who are at risk of thrombotic events but are concerned about bleeding risk to be treated, with a consequent reduction in strokes and possibly cardiovascular events as well.

Why Factor XI?

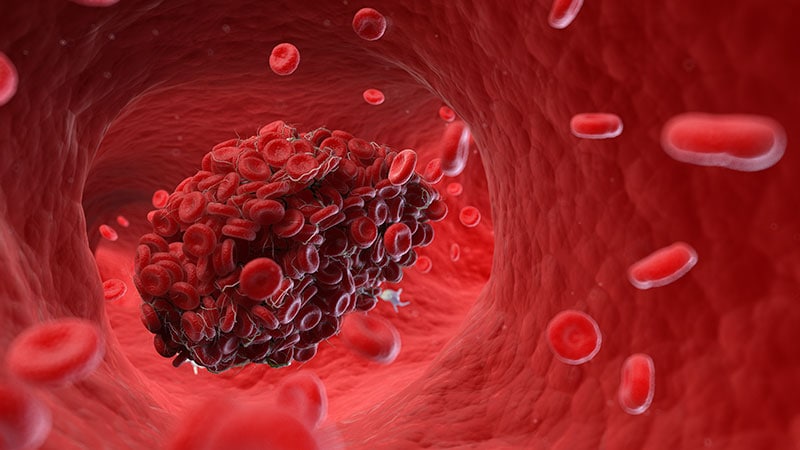

The hope that factor XI inhibitors will prevent pathologic thrombosis with a lower bleeding risk compared to other anticoagulants comes down to the role of factor XI in the coagulation cascade.

In natural physiology, there are two ongoing processes: (1) hemostasis ― a set of actions that cause bleeding to stop after an injury; and (2) thrombosis ― a pathologic clotting process in which thrombus is formed and causes a stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

In patients prone to pathologic clotting, such as those with AF, the balance of these two processes has shifted toward thrombosis, so anticoagulants are used to reduce the thrombotic risks. For many years, the only available oral anticoagulant was warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist that was very effective at preventing strokes but that comes with a high risk for bleeding, including intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding.

The introduction of the direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) a few years ago was a step forward in that these drugs have been shown to be as effective as warfarin but are associated with a lower risk of bleeding, particularly of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and fatal bleeding. But they still cause bleeding, and concerns over that risk of bleeding prevent millions of patients from taking these drugs and receiving protection against stroke.

John Alexander, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, a researcher active in this area, notes that “while the DOACs cause less bleeding than warfarin, they still cause two or three times more bleeding than placebo, and there is a huge, unmet need for safer anticoagulants that don’t cause as much bleeding. We are hopeful that factor XI inhibitors might be those anticoagulants.”

The lead investigator the AZALEA study, Christian Ruff, MD, professor of medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, explained why it is thought that factor XI inhibitors may be different.

“There’s a lot of different clotting factors, and most of them converge in a central pathway. The problem, therefore, with anticoagulants used to date that block one of these factors is that they prevent clotting but also cause bleeding.

“It has been discovered that factor XI has a really unique position in the cascade of how our body forms clots in that it seems to be important in clot formation, but it doesn’t seem to play a major role in our ability to heal and repair blood vessels.”

Another doctor involved in the field, Manesh Patel, MD, chief of cardiology at Duke University Medical Center, added, “We think that factor XI inhibitors may prevent the pathologic formation of thrombosis while allowing formation of thrombus for natural hemostasis to prevent bleeding. That is why they are so promising.”

This correlates with epidemiologic data suggesting that patients with a genetic factor XI deficiency have low rates of stroke and MI but don’t appear to bleed spontaneously, Patel notes.

Candidates in Development

The pharmaceutical industry is on the case with several factor XI inhibitors now in clinical development. At present, three main candidates lead the field. These are abelacimab (Anthos), a monoclonal antibody given by subcutaneous injection once a month; and two small molecules, milvexian (BMS/Janssen) and asundexian (Bayer), which are both given orally.

Phase 3 trials of these three factor XI inhibitors have recently started for a variety of thrombotic indications, including the prevention of stroke in patients with AF, prevention of recurrent stroke in patients with ischemic stroke, and prevention of future cardiovascular events in patients with ACS.

Alexander, who has been involved in clinical trials of both milvexian and asundexian, commented: “We have pretty good data from a number of phase 2 trials now that these factor XI inhibitors at the doses used in these studies cause a lot less bleeding than therapeutic doses of DOACs and low-molecular-weight heparins.”

He pointed out that in addition to the AZALEA trial with abelacimab, the phase 2 PACIFIC program of studies has shown less bleeding with asundexian than with apixaban in patients with AF and a similar amount of bleeding as placebo in patients ACS/stroke patients on top of antiplatelet therapy. Milvexian has also shown similar results in the AXIOMATIC program of studies.

Ruff noted that the biggest need for new anticoagulants in general is in the AF population. “Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common medical conditions in the world. Approximately 1 in every 3 people will develop AF in their lifetime, and it is associated with more than a fivefold increased risk of stroke. But up to half of patients with AF currently do not take anticoagulants because of concerns about bleeding risks, so these patients are being left unprotected from stroke risk.”

Ruff pointed out that the AZALEA study was the largest and longest study of a factor XI inhibitor to date; 1287 patients were followed for a median of 2 years.

“This was the first trial of long-term administration of factor XI inhibitor against a full dose DOAC, and it was stopped because of an overwhelming reduction in a major bleeding with abelacimab compared with rivaroxaban,” he noted. “That is very encouraging. It looks like our quest to develop a safe anticoagulant with much lower rates of bleeding compared with standard of care seems to have been borne out. I think the field is very excited that we may finally have something that protects patients from thrombosis whilst being much safer than current agents.”

While all this sounds very promising, for these drugs to be successful, in addition to reducing bleeding risk, they will also have to be effective at preventing strokes and other thrombotic events.

“While we are pretty sure that factor XI inhibitors will cause less bleeding than current anticoagulants, what is unknown still is how effective they will be at preventing pathologic blood clots,” Alexander points out.

“We have some data from studies of these drugs in DVT prophylaxis after orthopedic surgery which suggest that they are effective in preventing blood clots in that scenario. But we don’t know yet about whether they can prevent pathologic blood clots that occur in AF patients or in post-stroke or post-ACS patients. Phase 3 studies are now underway with these three leading drug candidates which will answer some of these questions.”

Patel agrees that the efficacy data in the phase 3 trials will be key to the success of these drugs. “That is a very important part of the puzzle that is still missing,” he says.

Ruff notes that the AZALEA study will provide some data on efficacy. “But we already know that in the orthopedic surgery trials, there was a 70% to 80% reduction in VTE with abelacimab (at the 150-mg dose going forward) vs prophylactic doses of low-molecular-weight heparin. And we know from the DOACs that the doses preventing clots on the venous side also translated into preventing strokes on the AF side. So that is very encouraging,” Ruff adds.

Potential Indications

The three leading factor XI inhibitors have slightly different phase 3 development programs.

Ruff notes that not every agent is being investigated in phase 3 trials for all the potential indications, but all three are going for the AF indication. “This is by far the biggest population, the biggest market, and the biggest clinical need for these agents,” he says.

While the milvexian and asundexian trials are using an active comparator ― pitting the factor XI inhibitors against apixaban in AF patients ― the Anthos LILAC trial is taking a slightly different approach and is comparing abelacimab with placebo in patients with AF who are not currently taking an anticoagulant because of concerns about bleeding risk.

Janssen/BMS is conducting two other phase 3 trials of milvexian in their LIBREXIA phase 3 program. Those trials involve post-stroke patients and ACS patients. Bayer is also involved in a post-stroke trial of asundexian as part of its OCEANIC phase 3 program.

Ruff points out that anticoagulants currently do not have a large role in the post-stroke or post-ACS population. “But the hope is that if factor XI inhibitors are so safe, then there will be more enthusiasm about using an anticoagulant on top of antiplatelet therapy, which is the cornerstone of therapy in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.”

In addition to its phase 3 LILAC study in patients with AF, Anthos is conducting two major phase 3 trials with abelacimab for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism.

Ruff notes that the indication of post-surgery or general prevention of VTE is not being pursued at present.

“The orthopedic surgery studies were done mainly for dose finding and proof of principle reasons,” he explains. “In orthopedic surgery the window for anticoagulation is quite short ― a few weeks or months. And for the prevention of recurrent VTE in general in the community ― those people are at a relatively low risk of bleeding, so there may not be much advantage of the factor XI inhibitors. Whereas AF patients and those with stroke or ACS are usually older and have a much higher bleeding risk. I think this is where the advantages of an anticoagulant with a lower bleeding risk are most needed.”

Alexander points out that to date, anticoagulants have shown more efficacy in venous clotting, which appears to be more dependent on coagulation factors and less dependent on platelets. “Atrial fibrillation is a mix between venous and arterial clotting, but it has more similarities to venous, so I think AF is a place where new anticoagulants such as the factor XI inhibitors are more likely to have success,” he suggests.

“So far, anticoagulants have had a less clear long-term role in the post-stroke and post-ACS populations, so these indications may be a more difficult goal,” he added.

The phase 3 studies are just starting and will take a few years before results are known.

Differences Between the Agents

The three factor XI inhibitors also have some differences. Ruff points out that most important will be the safety and efficacy of the drugs in phase 3 trials.

“Early data suggest that the various agents being developed may not have equal inhibition of factor XI. The monoclonal antibody abelacimab may produce a higher degree of inhibition than the small molecules. But we don’t know if that matters or not ― whether we need to achieve a certain threshold to prevent stroke. The efficacy and safety data from the phase 3 trials are what will primarily guide use.”

There are also differences in formulations and dosage. Abelacimab is administered by subcutaneous injection once a month and has a long duration of activity, whereas the small molecules are taken orally and their duration of action is much shorter.

Ruff notes: “If these drugs cause bleeding, having a long-acting drug like abelacimab could be a disadvantage because we wouldn’t be able to stop it. But if they are very safe with regard to bleeding, then having the drug hang around for a long time is not necessarily a disadvantage, and it may improve compliance. These older patients often miss doses, and with a shorter-acting drug, that will mean they will be unprotected from stroke risk for a period of time, so there is a trade-off here.”

Ruff says that the AZALEA phase 2 study will provide some data on patients being managed around procedures. “The hope is that that these drugs are so safe that they will not have to be stopped for procedures. And then the compliance issue of a once-a-month dosing would be an advantage.”

Patel says he believes there is a place for different formations. “Some patients may prefer a once monthly injection; others will prefer a daily tablet. It may come down to patient preference, but a lot will depend on the study results with the different agents,” he commented.

What Effect Could These Drugs Have?

If these drugs do show efficacy in these phase 3 trials, what difference will they make to clinical practice? The potential appears to be very large.

“If these drugs are as effective at preventing strokes as DOACs, they will be a huge breakthrough, and there is good reason to think they would replace the DOACs,” Alexander says. “It would be a really big deal to have an anticoagulant that causes almost no bleeding and could prevent clots as well as the DOACs. This would enable a lot more patients to receive protection against stroke.”

Alexander believes the surgery studies are hopeful. “They show that the factor XI inhibitors are doing something to prevent blood clots. The big question is whether they are as effective as what we already have for the prevention of stroke and if not, what is the trade-off with bleeding?”

He points out that even if the factor XI inhibitors are not as effective as DOACs but are found to be much safer, they might still have a potential clinical role, especially for those patients who currently do not take an anticoagulant because of concerns regarding bleeding.

But Patel points out that there is always the issue of costs with new drugs. “New drugs are always expensive. The DOACS are just about to become generic, and there will inevitably be concerns about access to an expensive new therapy.”

Alexnder adds: “Yes, costs could be an issue, but a safer drug will definitely help to get more patients treated and preventing more strokes, which would be a great thing.”

Patel has received grants from and acts as an advisor to Bayer (asundexian) and Janssen (milvexian). Alexander receives research funding from Bayer. Ruff receives research funding from Anthos for abelacimab trials, is on an AF executive committee for BMS/Janssen, and has been on an advisory board for Bayer.

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, X, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article