Researchers have developed a simple blood test that measures the body’s own immune response to improve diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common gynaecologic cancers, with the highest mortality rate. About 300,000 new cases are diagnosed globally each year, with an estimated 60% of women dying within five years after diagnosis.

The new study found that testing for a specific immune biomarker allows clinicians to identify whether growths on the ovaries are cancerous or not, without the need for tests like MRI scans or ultrasounds.

The clinical trial was conducted in two hospitals in Melbourne, Australia, with the results published in Scientific Reports.

Senior Author and Chief Investigator, RMIT University’s Professor Magdalena Plebanski, said the test could be an important diagnostic tool for assessing suspicious ovarian growths before operations.

“Our new test is as accurate as the combined results of a standard blood test and ultrasound,” said Plebanski, a Senior National Health and Medical Research Council Fellow at RMIT.

“This is especially important for women in remote or disadvantaged communities, where under-resourced hospitals may not have access to complex and expensive equipment like ultrasound machines or MRI scanners.

“It also means patients with benign cysts identified through imaging could potentially be spared unnecessary surgeries.

“This study looked at women with advanced ovarian cancer, but we hope further research could explore the potential for adding this biomarker to routine diagnostic tests at earlier stages of the disease.”

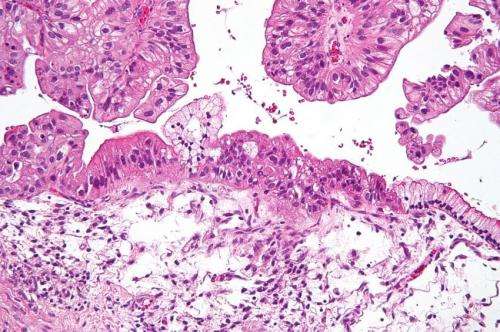

The study used an immune marker for inflammation (IL-6) together with cancer markers to detect epithelial ovarian cancer in blood. Results were validated across two separate human trial cohorts.

“Ovarian cancer is the deadliest women’s cancer, a statistic that has not changed in 30 years,” Plebanski said.

“Every day in Australia, four women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer and three will die from the disease.

“Developing tests that are simpler and more practical may help get more women to hospital for treatment more effectively, with the hope that survival rates will improve.”

Source: Read Full Article