Experiments led by researchers at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory have determined that several hepatitis C drugs can inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 main protease, a crucial protein enzyme that enables the novel coronavirus to reproduce.

Inhibiting, or blocking, this protease from functioning is vital to stopping the virus from spreading in patients with COVID-19. The study, published in the journal Structure, is part of efforts to quickly develop pharmaceutical treatments for COVID-19 by repurposing existing drugs known to effectively treat other viral diseases.

“Currently, there are no inhibitors approved by the Food and Drug Administration that target the SARS-CoV-2 main protease,” said ORNL lead author Daniel Kneller. “What we found is that hepatitis C drugs bind to and inhibit the coronavirus protease. This is an important first step in determining whether these drugs should be considered as potential repurposing candidates to treat COVID-19.”

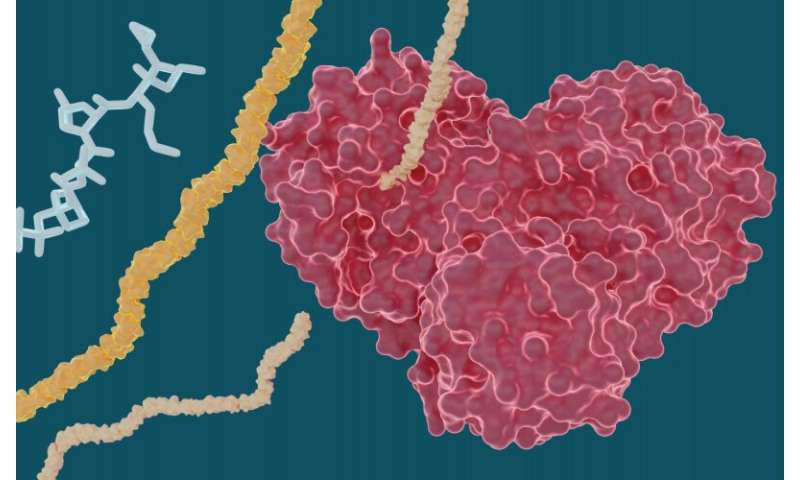

The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus spreads by expressing long chains of polyproteins that must be cut by the main protease to become functional proteins, making the protease an important drug target for researchers and drug developers.

In the study, the team looked at several well-known drug molecules for potential repurposing efforts including leupeptin, a naturally occurring protease inhibitor, and three FDA-approved hepatitis C protease inhibitors: telaprevir, narlaprevir and boceprevir.

The team performed room temperature X-ray measurements to build a three-dimensional map that revealed how the atoms were arranged and where chemical bonds formed between the protease and the drug inhibitor molecules.

The experiments yielded promising results for certain hepatitis C drugs in their ability to bind and inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 main protease—particularly boceprevir and narlaprevir. Leupeptin exhibited a low binding affinity and was ruled out as a viable candidate.

To better understand how well or how tightly the inhibitors bind to the protease, they used in vitro enzyme kinetics, a technique that enables researchers to study the protease and the inhibitor in a test tube to measure the inhibitor’s binding affinity, or compatibility, with the protease. The higher the binding affinity, the more effective the inhibitor is at blocking the protease from functioning.

“What we’re doing is laying the molecular foundation for these potential drug repurposing inhibitors by revealing their mode of action,” said ORNL corresponding author Andrey Kovalevsky. “We show on a molecular level how they bind, where they bind, and what they’re doing to the enzyme shape. And, with in vitro kinetics, we also know how well they bind. Each piece of information gets us one step closer to realizing how to stop the virus.”

The study also sheds light on a peculiar behavior of the protease’s ability to change or adapt its shape according to the size and structure of the inhibitor molecule it binds to. Pockets within the protease where a drug molecule would attach are highly malleable, or flexible, and can either open or close to an extent depending on the size of the drug molecules.

Before the paper was published, the researchers made their data publicly available to inform and assist the scientific and medical communities. More research, including clinical trials, is necessary to validate the drugs’ efficacy and safety as a COVID-19 treatment.

Source: Read Full Article