The COVID-19 pandemic has been defined not only by its outsized impact on the lives of people all over the world. In the U.S., the global pandemic has become a polarizing political issue, with misinformation flying far and wide on social media.

Now, new research suggests that politics played a significant role in who was dying early in the pandemic.

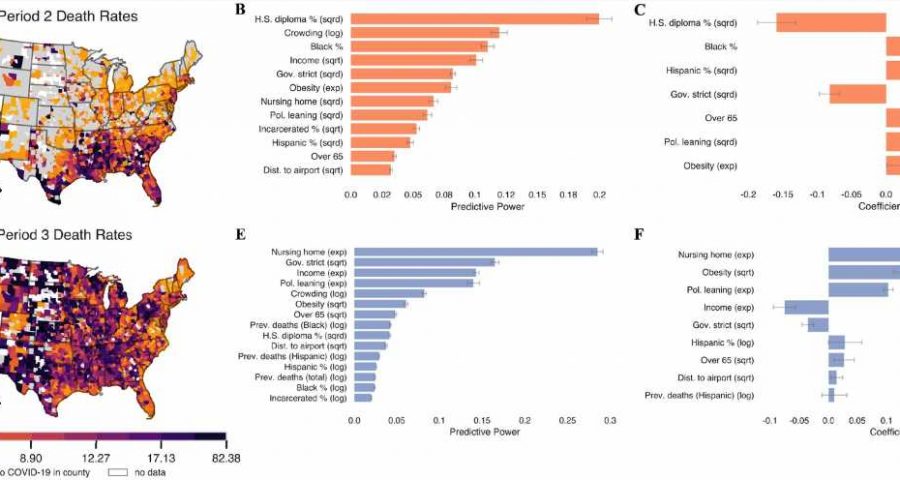

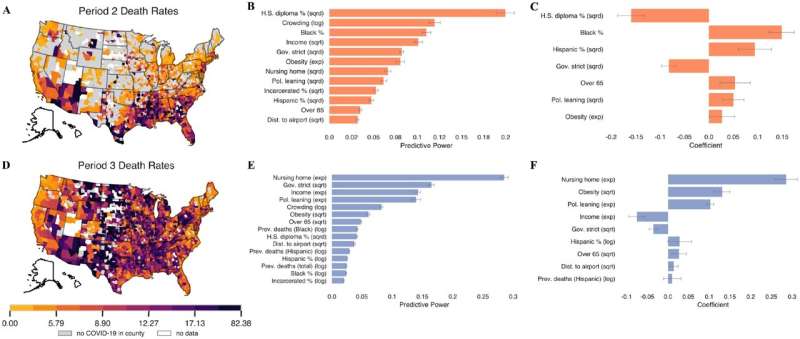

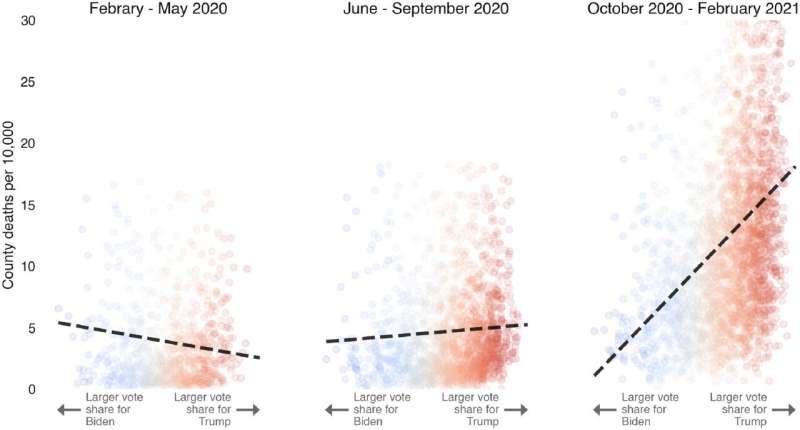

Mauricio Santillana, a professor of physics at Northeastern who specializes in epidemiology, and a team of researchers tracked trends in COVID-19 death rates during the first year of the pandemic. What they found was that deaths spiked in well-connected, Democrat-heavy cities early in 2020, but that by the first pandemic winter, deaths were about three times higher in Republican-leaning—and specifically Trump-leaning—areas of the country.

“In epidemiology, when you see 10% or 20% higher, you worry, but when you see threefold differences, then you panic,” Santillana says.

Strikingly, the researchers found that the median death rate for counties with the strongest Republican leaning was between 40% and 300% higher than the counties that leaned Democrat. Santillana says the stark differences are symptomatic of a public health crisis that has been heavily politicized.

“Something that became clear very early on in the pandemic was that people were listening to different voices,” Santillana says. “As a consequence, what started as a public health crisis started becoming a crisis that was determined more by the political affiliation that people had.”

In that way, the COVID-19 pandemic is different from past pandemics, he says. Typically, epidemiological models don’t even take into account the political leaning of communities. In this case, Santillana and the rest of the research team set out to document the vital role that political affiliation played in the devastation of the pandemic.

As part of their research, the team created models based on death counts from the country’s 2,000 counties that looked at factors ranging from socioeconomic status to obesity. Even when controlling for every other variable, the team found that political affiliation factored heavily in the death rate.

“We started monitoring how the different communities that aligned better with certain political affiliations started showing big differences in the way they were behaving, and we were concerned that would lead to different outcomes, some outcomes that would be regrettable, namely higher rates of mortality,” Santillana says. “We started realizing that political affiliation was an important factor in an epidemic outbreak, something that in prior outbreaks hadn’t been as explicit as it was during COVID-19.”

Between February 2020 and February 2021, the focus of this research, 462,475 people died from COVID-19 nationwide. Regionally, the story looks different in that time period.

In the Northeast, the majority of deaths, 51%, were in the first four months, when COVID-19 first arrived in the states and spread rapidly. Deaths decreased during summer 2020 as the CDC recommended mask wearing and states adopted mask mandates and social distancing policies were put in place. Meanwhile in the South, in the same period, deaths rose in the summer and peaked in the winter, with 57% of deaths occurring between October 2020 and February 2021. Deaths in the Northeast also rose slightly in winter 2020, but not to the same degree as the South. Santillana says this is when the link between behavior, inspired by information and misinformation, and its impact on COVID-19 outcomes can be most clearly seen. (The research draws on Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 data portal.)

“We realized that people who were listening to the stronger voices coming from the Republican party, specifically from Donald Trump, were dismissing the gravity of contracting COVID-19 and were dismissing the usefulness of masks and social distancing,” Santillana says. “Sadly, that led to much worse outcomes in those communities.”

Justin Kaashoek, the lead author on the research, says that based on the discourse around vaccines and boosters, the pandemic is still heavily politicized. However, he hopes this research can help avoid a similar story in the future.

There are still people who are dying from this disease, and there’s going to potentially, hopefully not in our lifetimes, be another pandemic,” Kaashoek says. “How do we make sure our political differences don’t get in the way of something that is strictly not political and shouldn’t be?”

During a panel organized by the University of Cambridge’s philosophy panel, Santillana admits his usual optimism was shaken when a member of the audience suggested that “what happened during COVID is intrinsic to societies working as political systems.”

“I have this optimistic perspective … that if we were only able to share the consequences in a transparent way, everyone should be able to digest the information and conclude that we should behave differently,” Santillana says.

“But in our current system, when vaccines were rolled out, even though we were presenting the studies showing their advantages … still people were choosing to believe or not believe. Can we really hope for a better outcome in the next [pandemic], which will occur at some point?”

The work is published in the journal PLOS Global Public Health.

More information:

Justin Kaashoek et al, The evolving roles of US political partisanship and social vulnerability in the COVID-19 pandemic from February 2020–February 2021, PLOS Global Public Health (2022). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000557

Journal information:

PLOS Global Public Health

Source: Read Full Article