Why Emil Zátopek?

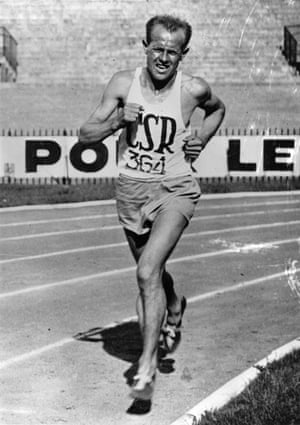

I think of Zátopek as the patron saint of runners. He didn’t just revolutionise his sport – he reinvented it. He rewrote the record books and redrew the boundaries of endurance, redefining the whole idea of what was humanly possible. No one else, before or since, has dominated distance running in a way that he did in the late 1940s and early 1950s. His achievements at the Helsinki Olympics will never be equalled. And he did all this with a crazy playfulness and generosity of spirit that made him perhaps the most loved Olympian of all time. The only comparable figure I can think of in 20th century sport is Muhammad Ali – yet Zátopek, unlike Ali, has barely been touched by biographers until now

Do you remember the first time you heard about him yourself?

I can barely remember a time when I didn’t know about Zátopek. I think I may even have been dimly aware of him as a child, from seeing news reports about the Prague Spring. But it was when I took up running myself, in my early 20s, that the idea of him really started to resonate. The idea of the stoical soldier, toughening himself up physically and mentally through sheer self-discipline, without losing his wit or humanity, was an inspiring one. I saw him as a role model for self-improvement – which is ridiculous, I know, but many other runners felt the same. The fact that he was also a martyr to Communist repression (this was before the fall of the Berlin Wall), and that no one really knew what had happened to him, just added to the mystery and romance. When I set out to write about Zátopek, I assumed that everyone knew his story – and I was shocked to find that most people, or most people under 40, had never heard of him.

What was he like to write about?

You’d think Zátopek would be an easy person to write a book about. He had such an amazing, colourful, inspiring, haunting story: a man who won five Olympic medals, set 18 world records, redefined the limits of human endurance, became a global byword for sportsmanship and generosity – and was driven into lonely obscurity by the communists after standing up for “socialism with a human face”. The story tells itself. The author just has to write it down. Yet in some ways, he’s also a terribly difficult subject. He’s certainly an intimidating one: the greatest, most charismatic, most written-about runner the world has ever seen. Writing his biography feels like a huge responsibility. You feel presumptuous taking it on.

Why do you think his name is less familiar now?

It was all a long time ago. Emil was born in 1922 and died in 2000. Contemporaries who survive are in their 90s, and they’re growing fewer all the time. Inevitably, some memories are more reliable than others. I found Dana Zátopková, Emil’s widow, wonderfully alert and communicative, but even she struggled to be precise about detailed sequences of events from 60 or 70 years ago. Other eyewitnesses were much shakier.There’s also the question of how reliable the evidence was in the first place. Most people in the Czech Republic, and perhaps in athletics too, have a Zátopek story they can tell you. The question is: where did it come from? Did they witness it themselves, or did they just hear it – and if so, from whom? A lot of myths just get repeated again and again – for example, the story that Emil used to carry Dana on his back when he trained, or that it was in 1968 that he gave his gold medal to Ron Clarke, after the Prague Spring and the Mexico Olympics. I’ve read that last one repeatedly, in bestselling books and respected newspapers of record. But that doesn’t make it true.

So did you find most of those legends were nonsense, then?

No, I think the most surprising thing I learnt was that, despite all the embellishments, an amazing amount of the Zátopek legend actually is true. No, he didn’t regularly carry Dana on his back, but he did do so at least once (and another time he did a whole training session with a small girl on his back). No, he didn’t train in the 800m corridor at military academy – but he did train in the deep sand of the giant indoor riding school. No, he didn’t give a gold medal to Ron Clarke in 1968, but he did do so in 1966. No, he didn’t give up his bed to an Australian journalist the night before the 10,000 metres at the Helsinki Olympics. But he did give up his bed to an Australian coach (Percy Cerutty) a few nights before the race – and got in trouble for allowing a western “spy” into the Communist bloc’s Olympic village. And so it goes on. This extraordinary, magical man really did exist. There really was a poor carpenter’s son from Moravia, with no special athletic talent, who built himself up through sheer hard work and inventiveness to be the most famous athlete the world had seen.

There really was a runner who single-handedly redrew the boundaries of his sport – yet maintained a lightness of heart and a generosity of spirit that made the world feel a warmer place during the darkest days of the cold war. He really was almost pathologically generous – at one point a Prague campsite started redirecting campers it didn’t have room for to the Zátopeks’ house, knowing that Emil would always offer them hospitality. And he really did defy the Soviet tanks in Wenceslas Square in August 1968, briefly stopping a superpower’s invasion in its tracks.

After that they broke him, of course. He spent years as an itinerant labourer, including a spell down a uranium mine, living in a caravan, far from his home and his beloved wife; and by the time he was rehabilitated he was a shadow of the man he had been. The story of the last years of his life is heartbreaking at times. Yet the one overwhelming fact that struck me again and again, wherever I went and whoever I spoke to, is that Emil Zátopek was loved. There was something child-like about him – he had an effect on people. “He lightened people’s lives,” was how one person put it. To me, that was the single most important thing about him.

Do you think that Zátopek’s story has any relevance to the modern runner?

Definitely. It’s not the training, though – fascinating though many runners find it. His innovations have been so thoroughly accepted, absorbed and developed that the details of what he did barely matter any more. Some runners still get obsessed by the numbers: did he do 80 fast 400m laps in a day or 100? How fast was each lap? How long were the recovery intervals? And so on. Those figures do exist – you’ll find some of them in my book. But I don’t think they really tell us much. A lot of his sessions were done without a stop-watch, over imprecisely measured distances – he did much of his training in the woods. A runner with more or less natural speed would derive a different degree of benefit from exactly replicating one of his sessions. And of course the kit was different, the tracks were different, the nutrition was different. There’s no comparison between what he did and what we can do.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=3c4Z8cbcIiA%3Fwmode%3Dopaque

What is still relevant, though, in my opinion, is his attitude. I don’t know if Emil ever really said, “A runner must run with dreams in his heart, not money in his pocket,” but it’s the sort of thing he could well have said, and it seems to me to be an incredibly timely message. But the ordinary runner might be also inspired by his sheer crazy commitment. Ultimately, we all know that you need to be a bit of a nutter to get the most out of yourself as a runner – and Emil was as bonkers as they come in that respect. It wasn’t just the running in heavy boots, the holding his breath until he passed out, the wearing three tracksuits at once while running through deep snow, the running in a bath full of laundry for two hours … It was also the philosophy: the idea that “Pain is a merciful thing – if it lasts without interruption, it dulls itself.”

That was the secret of his success as a runner: he trained himself to be tough in mind as well as body. “When a person trains once, nothing happens,” he said. “When a person forces himself to do a thing a hundred or a thousand times, he develops in ways more than physical. Is it raining? That doesn’t matter. Am I tired? That doesn’t matter either. Willpower becomes no longer a problem.”

I’ve found the mere thought of Zátopek’s example an energising, inspiring one during several decades as a runner. As Ron Clarke said: it’s not what he did, it’s the way he did it.

What’s your favourite piece of Zátopek wisdom?

“When you can’t keep going, go faster.” It’s bonkers, but it’s also the secret of everything. Just say it to yourself the next time you feel that you can’t keep going.

The quote you use for the title of the book, is that apocryphal too?

It’s something that Emil is supposed to have said on the starting line of the Olympic marathon in Melbourne in 1956. He may not have used those exact words, but he certainly said something along those lines. He was still recovering from a very recent hernia operation. He was way off peak fitness and in any case he was well past his best. The temperature was somewhere between 30 and 35 degrees. He knew that he could expect nothing from the race ahead except extreme physical agony. Yet he embraced it with a cheerful, friendly graveyard humour that seems to me to come close to capturing the essence of his nobility.

Do you think he has a natural heir at the moment? Someone who fits that mould, however differently they may now train/race?

I can’t think of anyone now running who compares to him. His nearest modern equivalent was Haile Gebrselassie – who managed to combine being an incredible runner with an infectiously cheerful, generous personality. And there have been plenty of others, such as Paula Radcliffe, who have looked to Zátopek as a role model. But there are so many differences between then and now. Zátopek put it well, towards the end of his life: “Today, the athlete is not an athlete. He’s the centre of a team – doctors, scientists, coaches and so on. Sometimes I ran like a mad dog, but it was very simple. It was out of myself.”

He seems to have been rather obsessed with 400m reps. Didn’t you ever wonder if he could have mixed it up a bit?

Yes, definitely. Apart from anything else, you wonder how he stuck at it. Didn’t he ever get bored? Perhaps there was a part of his personality that found the endless repetition reassuring. And it’s also worth bearing in mind that, for much of his career, he was under huge political pressure to keep winning. I don’t think he was exaggerating when he said that sometimes he ran in fear of being sent to prison if he lost. So he probably didn’t dare try anything that felt like easing off. Having said which, he did sometimes mix things up a bit: long slow runs in the mountains with Dana, messing around in the woods with a child on his back, jogging on the spot in a bath full of washing. He just doesn’t seem to have counted that kind of running – running without intensity and pain – as proper training.

Today We Die a Little : The Rise and Fall of Emil Zátopek, Olympic Legend by Richard Askwith is published by Vintage Publishing. Buy for £13.59 at the Guardian bookshop.

Source: Read Full Article